An initial economic assessment of the SSR Mining Inc. Securities Litigation

Introduction

This post contains an early case assessment of the SSR Mining Inc. Securities Case (1:24-cv-00739). The article discusses the potential damages in the case, the market efficiency indicators for the company, various loss causation issues, and potential settlement ranges.

This article is part of a series of standardized preliminary economic analyses of recently filed cases. In a separate publication I described the potential benefits from standardizing some preliminary case assessments. The opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of their company, employer, or its clients. This article is for general information purposes and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice. All tables and charts sourced from SCA iPortal are published with permission.

Summary of the SSR Mining Inc. Case

The case is based on the disaster at the SSR Mining’s Copler mine in Türkiye in February 2024. A large slip in the mine’s leach heap trapped a number of miners killing at least several of them as of this writing.

The complaint alleges that the “Defendants made false and/or misleading statements and/or failed to disclose that: (1) Defendants materially overstated SSR Mining’s commitment to safety and the efficacy of its safety measures; (2) SSR Mining engaged in unsafe mining practices which were reasonably likely to result in a mining disaster; and (3) as a result, Defendants’ statements about its business, operations, and prospects, were materially false and misleading and/or lacked a reasonable basis at all times.” The alleged misstatements are mainly in the company’s 10-K filings.

The complaint contains a number of disclosure events.

- In a 8-K filing on February 13, 2024, the company announced “a suspension of operations at the Çöpler mine as a result of a large slip on the heap leach pad. This event occurred in the morning of February 13, 2024 at approximately 6:30 am EST, and all operations at Çöpler have been suspended as a result.”

- “On February 16, 2024, after market hours, Reuters released an article entitled “SSR Mining says eight employees detained after Turkey mine landslide.”

- “On February 17, 2024, Mining.com published an article entitled ‘Turkey cancels SSR gold environmental permits after accident.’”

- “On Sunday, February 18, 2024, Sky News released an article entitled ‘Gold mine boss detained as search continues for missing miners trapped after huge landslide in Turkey.’… Also on February 18, 2024, the Company issued a press release in which it provided an update on the incident at Copler. In pertinent part, the Company did not contest that criminal charges filed against six Company employees were filed on legitimate grounds.”

- “On February 27, 2024, after market hours, Defendants conducted their earnings call for the Fourth Quarter of 2023. [] On this call, Defendant Antal stated that ‘[s]ix personnel are being detained and are facing charges in relation to the incident and we’re ensuring they receive the necessary support while respecting the Turkish legal process’. In pertinent part, Defendant Antal did not contest that the charges were filed on legitimate grounds.”

The class period of the case is from February 23, 2022, to February 28, 2024.

Figure 1: SSR Mining Inc. class period (SCA iPortal)

Aggregate Damages And Loss Causation

The Damage estimates in the SSR Mining case at this stage are highly speculative. The decisive factor in that regard will be the nature of the damage theory, and corresponding damage methodology, that will be applied. In addition, each damage theory comes with significant challenges when applied to a case of this type.

Some preliminaries. The SSR Mining (“SSRM”) case is an event-driven litigation. A detailed discussion of event driven cases is beyond the scope of this writing, but the interested reader can easily find discussions of this type of litigations.[1] A distinguishing feature of event-driven cases is that the direct victims are usually not the shareholders. In the case of SSR Mining Inc, the direct victims were the miners. However, based on statements made by the defendants before the accident and the fallout of the accident, the complaint alleges that shareholders were also damaged.

In typical event-driven cases, the “event” itself does not have to be misstated or omitted, though it is possible.[2] In the SSR Mining Inc. case, the heap slip only occurred at the end of the class period and was promptly announced.

Potentially Applicable Damage Theories

From an economic perspective, the main question is whether the damage to an investor in SSRM should include the entire stock price decline upon the occurrence of the leach heap slip or only a portion of it. Each of these will be discussed in more detail below. The reader should note that substantial differences of opinion exist within the legal and expert community not only about the assumptions and merits of the theories discussed below but even about their exact definitions. The discussion here is only provided to facilitate labeling and to put in context the subsequent computations.

- The idea that the entire decline associated with the occurrence of an event constitutes damage to an investor is generally associated with the “materialization-of-risk” damage theory. The “materialization-of-risk” damage theory generally posits that it is not the event that was misstated but the risk, i.e. likelihood, of the event occurring.[3] As a result of the misstated risk of the event occurring, plaintiff investors are misled into investing in the security and, therefore, suffer harm equal to the full decline that follows the event occurrence.

- The alternative damage computation, known as “out-of-pocket loss” theory, is based on the concept of price inflation. It generally assumes that the harm suffered by the investor is based on stock price inflation, i.e. the difference between the actual value paid by the investor and the true/but-for value of the stock if the true risk were known. In the case of misstated risk, the stock price inflation will necessarily depend on the difference between actually perceived risk and true risk (“risk difference”). Since the risk difference can be quite small, the harm computed under “out-of-pocket” loss theory is smaller than the full decline that follows the event occurrence.

While the two damage theories, and corresponding computation methodologies, are clearly distinct, the ultimate size of aggregate damages will most likely be somewhere in the middle between the corresponding estimates. First, it is far more likely, statistically speaking, that the aggregate damages will be negotiated in a settlement mediation than proved in formal damages reports. Second, the determination of which damage theory is applicable to which investors depends on unobservable variables. This is elucidated in the decision of the 5th Circuit court In Re BP PLC Securities Litigation with the following example.[4]

“Consider the following scenario: The true risk of a major spill was 2%, but BP’s statements had improperly represented the risk as 0.5%. Further imagine two different plaintiff-investors. The first is a low-risk pension fund, whose investment policy forbids investing in companies for whom the risk of a catastrophic event is greater than 1%. The second is a high-risk fund whose risk threshold is higher than 2%. Both plaintiffs invested in BP based on BP’s statements representing the risk as 0.5%. In this hypothetical, BP’s misstatements caused the low risk pension fund to make an investment forbidden under its policy. It would not have bought BP stock at all had it known the true risk of a catastrophe. This is the type of plaintiff the materialization-of-the-risk theory is designed to compensate. By contrast, the high-risk fund still might have purchased the stock, even had it known the “true” risk, though presumably at a lower price that accounted for the increased risk. For the second type of plaintiff, full materialization-of-the-risk damages would prove a windfall.” (emphasis added)

In short, the “materialization-of-risk” theory which awards the entire event-date price decline is applicable to investors who would not have purchased the stock had they known the true level of risk. For the rest of the investors, the relevant damage computation should be based on the “out-of-pocket loss” theory. In reality, however, the class most likely contains both types of investors. What is more important is that it is practically impossible to determine which investors fall into such a category.

First, few if any investors have an explicit policy based on the probability of the specific type of catastrophic risk. It is possible that some institutional asset managers do but no retail investor can have a credible policy of this type.

Second, even if an institutional investor has such an explicit policy, it would be highly speculative to determine the risk of the leach heap slide in the actual or but-for worlds. The speculative nature of the amount of risk embedded in the SSRM price is a problem for both determining the applicable damage methodology and the estimation of the aggregate damages under “out-of-pocket loss” theory.

Finally, note that the court in the SSR Mining case does not have to consider the investor grouping outlined in the example above. For these reasons, I simply outline the likely damages under both theories without trying to predict the outcome for the SSR Mining case.

Aggregate Damages Under Materialization-of-Risk Theory

According to the 5th Circuit decision In Re BP PLC Securities Litigation, the damages under “materialization-of-risk” theory equal the price decline upon the occurrence of the event. The 5th Circuit decision states, in relation to the example cited above, that “for the first plaintiff, who would not have purchased the stock absent the misrepresented risk, the decline in the stock’s value when the risk actually materialized may well be causally linked to the misrepresentation, in which case that full stock price decline following the materialization of the catastrophic event could constitute a valid economic loss.”

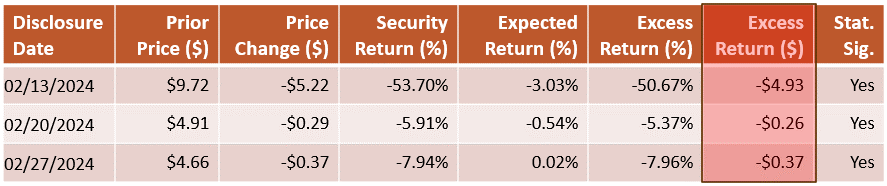

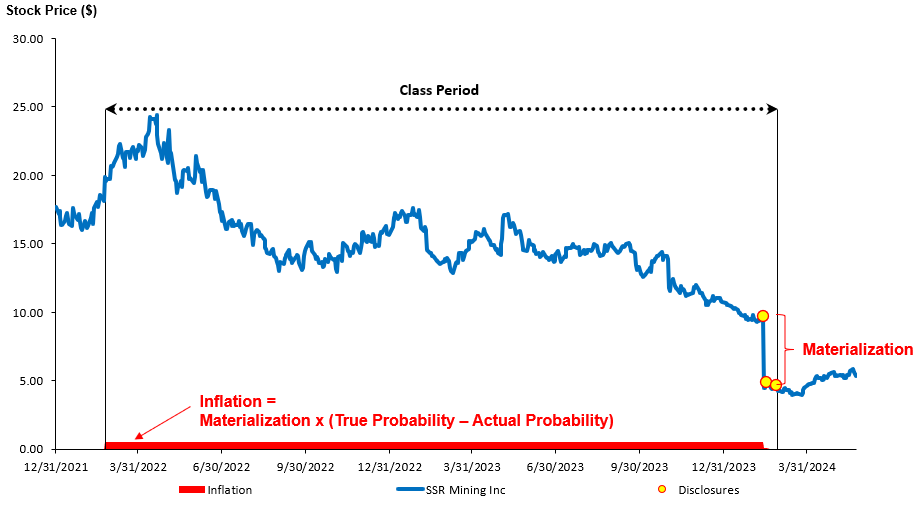

Under this definition, the inflation ribbon would look like Figure 2 – the inflation/harm is equal to the realization of the risk, i.e. the sum of all excess price declines on all alleged disclosure dates.[5] The excess price declines on the disclosure dates are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2: Computation of Stock Price Inflation Band Under Materialization-of-Risk Theory (SCA iPortal)

Figure 3: SSR Mining Inc. Excess Return Computation over February 13-27, 2024 (SCA iPortal)

Aggregate damages are shown in Figure 4. Damages are computed under the assumptions disclosed in the Appendix: Damages Assumptions, most notably – the use of constant dollar inflation as a proxy for the loss attributable to realization of the risk. Damages are in the order of $679 million (without the 90-day Lookback Cap) and $650 million (with the 90-day Lookback Cap). The 90-day Lookback Cap refers to the provision in the PSLRA that damages to any investor who holds or sells their shares after the end of the class period, cannot exceed the difference between the purchase price and a selling price representing a running 90-day average of the stock price.[6]

It should be noted that damages include only purchases that were sold after a corrective disclosure or held at the end of the class period. Hence, the “In-and-out” damages in Figure 4 are only damages to investors who purchased during the class period and sold their shares after February 13, 2024, at a loss that may be less than the full loss on the alleged disclosure dates.

Figure 4: Plaintiff-Style Aggregate Damages under Materialization of Risk Theory (SCA iPortal)

As already mentioned above, the main problem for implementing the “materialization-of-risk” damage methodology is the inability to pinpoint convincingly the investors to which it applies.

Aggregate Damages Under Out-of-Pocket Loss Theory

The “materialization-of-risk” damage methodology was applicable to investors who would not have bought SSRM stock had they known the true level of accident risk. On the other hand, the “out-of-pocket” loss methodology is applicable to those investors that, as the 5th Circuit Court described, “still might have purchased the stock, even had it known the “true” risk, though presumably at a lower price that accounted for the increased risk.”

While the theory is conceptually clear, in practice, estimating the actual or true likelihood of the accident occurring will be a controversial estimate under any circumstances. In this article, I use illustrative values with convenient round numbers to describe the computation.

The illustrative example is as follows. Assume that the actual market expectation of a leach heap slide accident occurring was inappropriately guided by SSR Mining to be 0.1%, i.e. extremely unlikely. Assume also that the true risk of the accident occurring was 10.1%, a likely excessive estimate I assume only to highlight the effect of the risk difference. Had the market been informed of the true likelihood of the event occurring, the SSRM price would have been lower $0.56 by the product of:

- The total disclosure-date decline of $5.56, and

- The difference in likelihoods, or risk difference, of 10% (= 10.1% -0.1%)

In other words, under the hypothetical example above, the “out-of-pocket” price inflation is 10%, i.e. 1/10th, of the total materialization of risk on the disclosure dates. This relationship is illustrated in Figure 5. In aggregate terms, the scenario above would result in damages of approximately $69 million, or roughly 1/10th of the “materialization-of-risk” damages.

Figure 5: Figure 3: Illustrative Computation of Stock Price Inflation Band Under Out-of-Pocket Loss Theory (SCA iPortal)

The important concept to notice is that the “out-of-pocket” damages are a fraction of the “materialization-of-risk” damages. The “fraction” is the risk difference between the actual and true risk of the accident. As shown, if the risk difference was 10%, the “out-of-pocket” damages would be 10% of the “materialization-of-risk” damages, or $69 million. If the risk difference was 1%, the “out-of-pocket” damages would be 1% of the “materialization-of-risk” damages, or $6.9 million.

As already mentioned above, the main problem with implementing the “out-of-pocket” damage theory is the estimation of the appropriate actual or true risk of an accident. This risk difference is not only unobserved but may also not be static as I assume in my estimation above.

In summary, estimating the aggregate damages is speculative. At the settlement stage the damages are likely to be negotiated rather than proven, or at least more so than in cases with a single applicable damage theory.

Other Sensitivities of the Aggregate Damages

The choice of (or the win for) one of the damages theories above is likely to be the main determinant of the size of the aggregate damages. Few other assumptions have any significant impact on the size of the aggregate damages.

Assumptions that have impact on the aggregate damages may affect the computation of damages per share, the counting of damaged shares, or both.

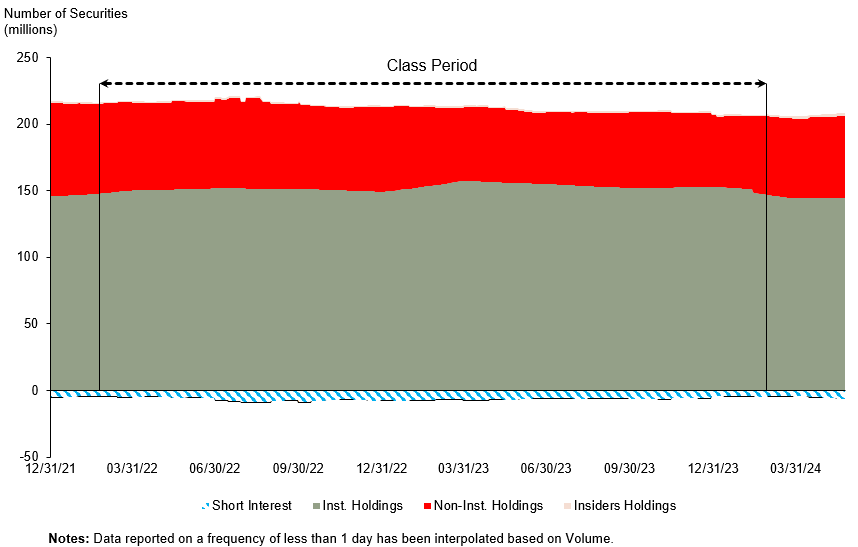

An assumption that may cause aggregate damages to be higher, is the inclusion of damages on the “short interest” in the stock. The short interest is the number of shares that were sold by short sellers in the market. Since short sellers sell securities they do not own, the resulting sales create de facto artificial shares which cannot be distinguished from any other share. Since the short interest in SSRM sock reached 4.2 million to 4.7 million during the class period (see Figure 6), the aggregate damages including those shares (under “materialization-of-risk” theory) rise to a little over $700 million.

Figure 6: SSR Mining Share Composition (SCA iPortal)

Assumptions that may cause aggregate damages to be lower include the inclusion of gains on shares purchased before the class period or limiting damages per share to the trading loss incurred by the investor in the transaction.

The inclusion of gains on pre-class period purchases was adopted in the Household settlement. The assumption relies on the fact that shares purchased before the class period are not inflated by definition. Therefore, if these shares are sold during the class period at an inflated (by definition) price, the investor realizes a gain which can offset other losses the investor may have.

The cap on damages per share to be no larger than the investor’s trading loss limits the damage per share to the lower of (a) the change in price inflation or (b) change in price, between the purchase date and the sale date.

Including both assumptions in the computation of aggregate damages for the SSRM case results in damages of $595.2 million (without 90-day Lookback Cap) or $581.7 million (with the 90-day Lookback Cap).

Class Certification – Market Efficiency

Defendants usually face an uphill battle in fighting market efficiency on US exchange listed securities. SSRM is not an exception to that rule but, as I show below, it does present some opportunities for defense experts. In the discussion below, I cite the test and the corresponding numeric values, and compare those value to benchmarks provided in a paper by Bhole, Surana and Torchio (2020).[7]

Note that the authors of the paper propose, without supporting analysis, that a factor which is above the 10th percentile for all stocks in the direction required for efficiency should be considered to be indicative of efficiency. For example, if the Cammer turnover statistic for SSRM is higher than the turnover of 10% of the US-listed securities, then Bhole, Surana and Torchio (2020) argue that it should be considered supportive of market efficiency.

Cammer Factors:

Cammer 1: Weekly Volume Turnover

Purpose: According to Cammer v Bloom “[t]he reason the existence of an actively traded market, as evidenced by a large weekly volume of stock trades, suggests there is an efficient market is because it implies significant investor interest in the company.” The decision states that “turnover measured by average weekly trading of 2% or more of the outstanding shares would justify a strong presumption that the market for the security is an efficient one; 1% would justify a substantial presumption.”[8]

Result: Average ratio of weekly trading volume to securities outstanding over the class period is 4.95%. See Figure 7. Excluding the extraordinary spike in turnover during the weeks February 13 and February 20, 2024, the average turnover is 4.3%. Both of these estimated, according to Cammer, justify “a strong presumption that the market for the security is an efficient one.” Both values are also over the 95th percentile among US listed stocks.

Figure 7: Weekly Trading Volume (SCA iPortal)

Cammer 2: Number of Analysts Following the Stock

Purpose: According to Cammer v Bloom, “it would be persuasive to allege a significant number of securities analysts followed and reported on a company’s stock during the class period. The existence of such analysts would imply, for example, the [company’s] reports were closely reviewed by investment professionals, who would in turn make buy/sell recommendations to client investors.”[9]

Result: Average number of analysts covering the company over the class period is 6.4. See Figure 8. This is just above the 50th percentile (aka median) of US listed firms.

Figure 8: Number of Securities Analysts (SCA iPortal)

Cammer 3: Number of Market Makers

Purpose: According to Cammer v Bloom, “[t]he existence of market makers and arbitrageurs *1287 would ensure completion of the market mechanism; these individuals would react swiftly to company news and reported financial results by buying or selling stock and driving it to a changed price level.”

However, the “Market makers count” was criticized for its misleading nature as early as 5 years after the Cammer decision. Barber, Griffin and Lev (1993) concluded that “apparently, market makers just “make a market” in the stock, namely match buy and sell orders, without contributing to the information available about the stock.”[10] The definition of a “market maker” also differs across market structures, e.g., NYSE vs NASDAQ. As a result, economic experts have used ‘proxies’ for what the Cammer decision envisioned are “individuals would react swiftly to company news and reported financial results by buying or selling stock and driving it to a changed price level.”[11] The most common such ‘proxies’ are the percentage of institutional investors holding a security and the short interest as a fraction of the shares outstanding.

Result 1: The average percentage of SSRM stock held by institutional investors during the class period was 73.6%. See Figure 9. This is above the 50th percentile (aka median) of US listed securities.

Result 2: The average short interest of SSRM stock as fraction of securities outstanding during the class period was 3.08%. See Figure 9. This is almost exactly the 50th percentile (aka median) of US listed stocks.

Figure 9: Sophisticated Investors (SCA iPortal)

Cammer 4: Eligibility to file SEC Form S-3

Purpose: According to Cammer v Bloom, “it would be helpful to allege the Company was entitled to file an S-3 Registration Statement in connection with public offerings or, if ineligible, such ineligibility was only because of timing factors rather than because the minimum stock requirements set forth in the instructions to Form S-3 were not met.” [12]

Result: SSRM did not file SEC form S-3 during or close to the class period. However, SSRM appears to satisfy the main criteria for eligibility to file the form. SSRM’s market capitalization was above the minimum required ($75 million) for filing form S-3 throughout the class period (see Figure 12). The stock had traded on a US exchange for longer than 12 months and the company was up to date with its financial filings.

Cammer 5: Cause-and-Effect Relationship Between Material News and Stock Returns

Purpose: The Cause-and-Effect (aka Fifth Cammer) Factor is considered, by most experts and courts, the most direct test of market efficiency. Cammer v Bloom states “it would be helpful to a plaintiff seeking to allege an efficient market to allege empirical facts showing a cause-and-effect relationship between unexpected corporate events or financial releases and an immediate response in the stock price. This, after all, is the essence of an efficient market and the foundation for the fraud on the market theory.”[13]

There are a number of tests that can be applied to this factor. Two standardized tests are presented below:

Result 1: Percent of earnings announcements with statistically significant price reaction during the class period: 59% (10 out of 17). See Figure 10.

This is a result of an event study on the days of earnings releases by SSRM during the class period. Earnings days are the most commonly used dates with potentially material new information. It should be noted, however, that the use of earnings announcements needs to be reviewed further by economic experts to determine whether the lack of statistically significant reaction to any of them is scientifically expected or surprising. Analysis needs to be conducted to determine if the earnings announcements were in line with expectations, contained earnings surprises or material new information such as future guidance. This analysis will involve significant amount of expert judgment.

Note: The reason SSRM had so many “earnings events” during the class period is that it reported earnings before market open and held the earnings call or presentation after the market close. Thus, the impact of the earnings information is potentially spread over a two-day period. It is reasonable to argue that the most important earnings-related information came out in the initial earnings release before the market open. There are 9 of these events in the class period, and 8 of them (or 89%) are statistically significant.

Figure 10: Earnings Dates Event Study (SCA iPortal)

Result 2: The correlation between volume and security returns IS statistically significant. See Figure 11.

This test assumes that volume is a proxy for news flow.[14] Thus, a test of the correlation between returns and volume is arguably a test of the cause-and-effect between information flow and returns. According to Bhole, Surana and Torchio (2020), over 98% of US listed stocks exhibit statistically significant correlation between daily returns and volumes.

Figure 11: Return – Volume Regression (SCA iPortal)

Krogman Factors

Krogman 1: Market Capitalization

Purpose: According to Krogman v. Sterritt, “[m]arket capitalization, calculated as the number of shares multiplied by the prevailing share price, may be an indicator of market efficiency because there is a greater incentive for stock purchasers to invest in more highly capitalized corporations.”[15]

Results: The average market capitalization of SSRM stock during the class period was $3.1 billion, though it varied between $5.1 billion and $870 million. The $3.1 billion average is above the 50th percentile (aka median) but below the 75th percentile of US listed stocks. See Figure 12.

Figure 12: SSR Mining Inc. Market Capitalization (SCA iPortal)

Krogman 2: Bid-ask Spread

Purpose: According to Krogman v Sterritt, “A large bid-ask spread is indicative of an inefficient market, because it suggests that the stock is too expensive to trade.”[16]

Results: The average Bid-Ask Spread of a SSRM Inc Ordinary Share was, on average, $0.01, or 0.08% of the security price. See Figure 13. An average bid-ask spread of 0.08% is below the 50th percentile of bid-ask spreads of US listed companies. (Note: For Bid-Ask spreads LOWER is better)

Figure 13: SSR Mining Inc. Bid-Ask Spread (SCA iPortal)

Krogman 3: Public float

Purpose: According to Krogman v Sterritt, “Because insiders may have private information that is not yet reflected in stock prices, the prices of stocks that have greater holdings by insiders are less likely to accurately reflect all available information about the security.”[17]

Result: The average Public Float of SSRM Inc Ordinary Shares was, on average, 205.6 million, or 99.4% of the outstanding securities. See Figure 14. There is no benchmark for public float shares of outstanding stock of which I am aware.

Figure 14: SSR Mining Inc. Public Float (SCA iPortal)

Autocorrelation

Purpose: Autocorrelation is a term used to describe predictability of future returns by current returns. The presence of autocorrelation, also known as serial correlation, is inconsistent with market efficiency because it implies that not all value-relevant information is quickly incorporated into the security price. Therefore, autocorrelation tests have been a staple of market efficiency testing since the introduction of the Efficient Markets Hypothesis in 1970.[18] Courts have also relied on autocorrelation results in establishing market efficiency.[19]

Result: There is NO evidence of statistically significant autocorrelation, i.e., predictability, in both the SSRM daily raw and excess returns. See Figure 15. According to the benchmark in Bhole, Surana, and Torchio (2020), about 27% of US listed stocks had a statistically significant autocorrelation.

Figure 15: Autocorrelation Regression (SCA iPortal)

Other Class Certification Considerations

Cases in which “materialization-of-risk” damages theory is applicable have to consider the implications of the theory for other Class Certification requirements as well, not just the requirement of Market Efficiency for reliance. While these questions stretch into the realm of legal arguments, which I try to avoid, some are important enough to include here and I outline them based on direct citations from the In Re BP Securities Litigation decision by the 5th Circuit.

The 5th Circuit concluded that “[u]nlike the stock inflation model, the materialization-of-the-risk model cannot be applied uniformly across the class, as Comcast requires, because it lumps together those who would have bought the stock at the heightened risk with those who would not have. It also presumes substantial reliance on factors other than price, a theory not supported by Basic”.[20]

The reason the 5th Circuit concluded that the “materialization-of-risk” theory “lumps together those who would have bought the stock at the heightened risk with those who would not have” was explained by the same example I cited previously. In short, in order for the “materialization-of-risk” damages model to compensate investors correctly, one needs to know investor-specific information like their “risk tolerance” or “risk aversion.” According to the 5th Circuit decision, this violates the commonality requirement.

Additional Loss Causation and Price Impact Points

As already discussed in the Aggregate Damages And Loss Causation section, some of the most important loss causation arguments will focus on the appropriate damage theory and damage methodology for the case.

In this section, I only add other loss causation (and price impact) points that come up during the analyses of the alleged disclosures in the complaint. These include analysis of the statistical significance of the alleged disclosures and preliminary review of the news on these dates.

A preview of the results, all of which require more detailed expert analysis, is that the loss causation or price impact arguments in the complaint are likely to be supported by the analysis of the alleged disclosures. There may be substantive arguments whether all alleged disclosure statements are corrective disclosures of the alleged misstatements and omissions. However, such arguments require both legal opinions and more detailed economic analyses.

Event Study

The event study is a typical starting point of any analysis of loss causation or price impact.

In the SSR Mining Inc. securities case, the complaint alleges 5 separate disclosures whose impact is measured over 3 days under the assumptions of an efficient market.

- The impact of the disclosure after the market closed on February 13, 2024, is measured on February 14, 2024.

- The impact of the disclosures on February 16 (after close), 17 and 18, 2024 are measured on February 20, 2024.

- The impact of the disclosure after the market close on February 27, 2024, is measured on February 28, 2024.

The results are shown in Figure 16. Notably, all alleged disclosure dates produced highly statistically significant excess returns, i.e. returns adjusted for market and industry factors. This suggests that it is very likely that material information (including the alleged disclosures in the complaint) was released on each of these dates, lending potential support to the allegations in the complaint.[21] This result is robust to the selection of industry indexes as well, which SCA iPortal allows to check easily.

Figure 16: Disclosure Dates Event Study (SCA iPortal)

Of course, the high probability that material information was released on these 3 dates does not automatically prove that the price declines are driven by the alleged disclosures or that there is no other / confounding information released on these dates. For that reason, I briefly look at the main intraday price movements and news releases associated with them.

Intraday Price and News Headlines Analysis on February 13-14, 2024

The impact of the disclosure after the market closed on February 13, 2024, is measured on February 14, 2024. The intraday price on February 14, 2024, is shown in Figure 17. As the figure shows, the stock price declined immediately upon the market open which is consistent with news arrival between the prior day’s close time and the current date’s opening time. There are two potentially material news announcements that came out in this period.

The first one is the alleged disclosure, i.e. announcement of the leach heap slide in the Copler mine after the close on February 13, 2024. The second is the SSR Mining Inc Long Term Production Guidance Call, which contained detailed descriptions and forecasts for the operation of the 4 main mining operations of SSR Mining Inc. The Long-Term Production Guidance Call was released in a SEC form 8-K before the open on February 14, 2024.

Whether any confounding news releases exists on February 14, 2024, depends on whether the information in the Long-Term Production Guidance Call was in line with the market consensus. Such detailed analysis needs to be performed by the economic experts of both sides. In this preliminary review, I use “reverse inference” based on the fact that the vast majority of the news headlines on February 14, 2024, attributed the stock price decline to the alleged disclosures rather than the Long-Term Production Guidance Call.

Figure 17: Intraday Price on February 14, 2024 (SCA iPortal)

Intraday Price and News Headlines Analysis on February 16-20, 2024

The complaint alleges several disclosures between the market close on February 16, 2024, and February 18, 2024, all of which are reflected in the stock price reaction on February 20, 2024. As already mentioned above, the Event Study confirmed that the excess return on February 20, 2024, is statistically significant.

Figure 18 shows that the intraday price impact on February 20, 2024, is also consistent with the release of material news between the market close on February 16, 2024, and the market open on February 20, 2024. The stock price declines immediately at the market open and after that.

In addition, virtually all news leading up to the decline on February 20, 2024, appear to be related to the Copler mine incident, fallout and investigation.

Figure 18: Intraday Price on February 20, 2024 (SCA iPortal)

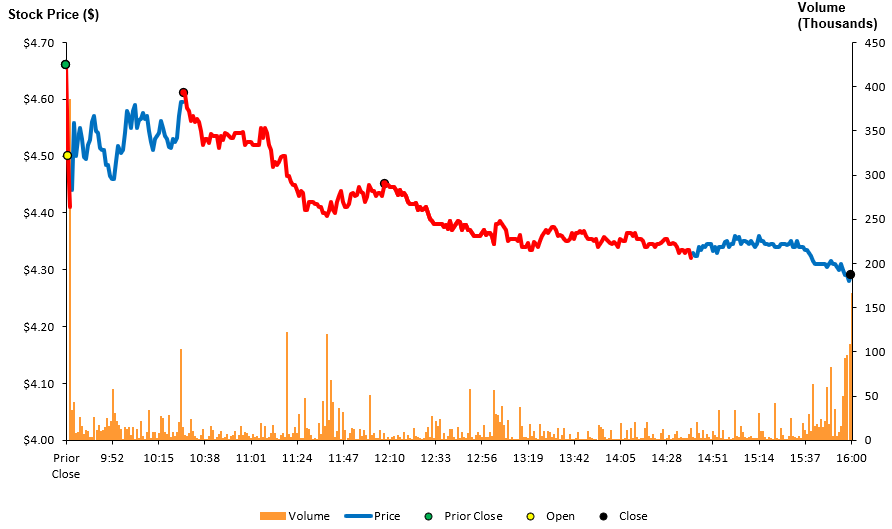

Intraday Price and News Headlines Analysis on February 27-28, 2024

The complaint alleges that after the market closed on February 27, 2024, SSRM released their earnings results. As already mentioned above, the Event Study confirmed that the excess return on February 28, 2024, is statistically significant.

Figure 19 shows that the intraday price impact on February 28, 2024, is also consistent with the alleged disclosure occurring after the market close on February 27, 2024. The news headlines on February 28, 2024, focused on the financial impact of the incident, including the suspension of the dividend and share repurchases and the withdrawal of the FY2024 and long-term guidance. All of these items are claimed by the complaint to represent disclosure of inflation due to the misstatements during the class period.

Figure 19: Intraday Price on February 28, 2024 (SCA iPortal)

Settlement Analysis

The expected settlement in the SSR Mining Inc. Securities Litigation, at the outset of the case, is approximately $9.8 million. See Figure 20. This is approximately 1.4% of the roughly $679 million damage estimate under the “materialization-of-risk” theory. Interestingly, this settlement is in line with the historical experience for cases with similar damage estimates as documented in research reports by NERA (1.7%) but lower than the estimates published in the latest report by Cornerstone research (3.3%-4.6%).[22] Reconciliation of these results is well beyond the scope of a preliminary analysis but can very well be explained by differences in the computations of plaintiff damages between NERA and Cornerstone (and SCA iPortal), or the set of cases included in these reports.

The prediction interval from the 25th to 75th percentiles (50% confidence) ranges from $5.0 to $19.1 million. The prediction interval is computed via an econometric model calibrated on similar settled cases filed since 2005. The prediction interval takes into account both the uncertainty of the calibrated model parameters and the existence of unpredictable factors in the settlement of every case.

Figure 20: Settlement Prediction Interval (SCA iPortal)

Appendix: Damages Assumptions

- The Plaintiff-style damages are the product of “damages per share” and “damaged shares”

- Damages per share during the class period are computed as the difference in purchase price inflation and sale price inflation.

- price inflation is computed using the sum of the disclosure-days’ excess dollar returns.

- Price inflation is assumed to be a constant dollar inflation. Constant dollar inflation is a constant dollar amount between the disclosure dates.

- Excess dollar returns (i.e., price changes adjusted for market and industry effects) are computed based on a market model regression using S&P 500 Index (market index) and S&P 500 Gold Index.

- Damages per share for shares sold after the end of the class period are based on the following assumptions:

- Without the 90-day Lookback Cap: Damages per share are difference between the purchase price inflation and the price inflation at the end of the class period ($0).

- With the 90-day Lookback Cap: As stipulated in the regulation, the damage per share is the smaller of (a) and the difference between the purchase price and the average price over a period of at most 90-days following the class period.

- Damaged shares are computed via multi-trader model:

- The model counts the number of damaged shares, subject to assumptions, from institutional holdings data.

- The model applied a 2-trader trading model for the non-institutional holdings.

See also, Emily Strauss, Is Everything Securities Fraud?, 12 U.C. Irvine L. Rev. 1331 (2022). Available at: https://scholarship.law.uci.edu/ucilr/vol12/iss4/9 ↑

Exceptions do exist. For example, In re BP P.L.C. Securities Litigation, allegations involved both pre-spill misstatements (about the likelihood of the event occurring) and post-spill allegations (about the spill rate, i.e. size of the event). ↑

This article is not intended to be a detailed discussion of the “materialization-of-risk” theory. The “materialization-of-risk” theory has other distinguishing characteristics. For example, the “materialization-of-risk” theory does not require an explicit disclosure that the risk was misstated. The realization of the event, along with any investigation results, is assumed to constitute a corrective disclosure ↑

One should, however, note that the BP case did not reach the damages report stage. The damage theories and damage computations were discussed at length during the class certification arguments. See, Decision, Appeals from the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas, 14-20420. ↑

Note that the figure is illustrative as the period of disclosures between February 13, 2024, and February 28, 2024, includes both disclosure- and non-disclosure dates. ↑

“In any private action arising under this chapter in which the plaintiff seeks to establish damages by reference to the market price of a security, if the plaintiff sells or repurchases the subject security prior to the expiration of the 90-day period described in paragraph (1), the plaintiff’s damages shall not exceed the difference between the purchase or sale price paid or received, as appropriate, by the plaintiff for the security and the mean trading price of the security during the period beginning immediately after dissemination of information correcting the misstatement or omission and ending on the date on which the plaintiff sells or repurchases the security.” 15 U.S. Code § 78u–4 – Private securities litigation ↑

Bharat Bhole, Sunita Surana. & Frank Torchio (2020), “Benchmarking Market Efficiency,” 2020 U. Ill. L. Rev. Online 96. While the paper uses data up to 2018, the 3-year measurement periods provide some credibility to the benchmark values. ↑

Cammer v. Bloom, 711 F. Supp. 1264 (D.N.J. 1989). ↑

Cammer v. Bloom, 711 F. Supp. 1264 (D.N.J. 1989). ↑

- Barber, Brad M., Paul A. Griffin, and Baruch Lev. “The fraud-on-the-market theory and the indicators of common stocks’ efficiency.” J. Corp. L. 19 (1993): 285. ↑

Cammer v. Bloom, 711 F. Supp. 1264 (D.N.J. 1989). ↑

Cammer v. Bloom, 711 F. Supp. 1264 (D.N.J. 1989). ↑

Cammer v. Bloom, 711 F. Supp. 1264 (D.N.J. 1989). ↑

For review of studies on the topic, see Jonathan M. Karpoff, The Relation Between Price Changes and Trading Volume: A Survey, 22(1) J. FIN. & QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS 109, 121 (1987). See also Chen, Gong-Meng, Michael Firth, and Oliver M. Rui. 2001. The dynamic relation between stock returns, trading volume, and volatility. Financial Review 36: 153–74. ↑

Krogman v. Sterritt, 202 F.R.D. 467, 474 (N.D. Tex. 2001). ↑

Krogman v. Sterritt, 202 F.R.D. 467, 474 (N.D. Tex. 2001). ↑

Krogman v. Sterritt, 202 F.R.D. 467, 474 (N.D. Tex. 2001). ↑

Fama, Eugene F. “Efficient capital markets.” Journal of finance 25.2 (1970): 383-417. ↑

In re PolyMedica Corp. Sec. Litig., 453 F. Supp. 2d 260, 276-78 (D. Mass. 2006)) ↑

Decision, Appeals from the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas, 14-20420. ↑

It should be noted that the statistical significance of the events impacting February 20, 2024 are based on a model which excludes the impact of February 14, 2024, from the calibration of the Event Study model. This is a standard assumption in Event Study modeling. ↑

See Cornerstone Research, “Securities Class Action Settlements: 2023 Review and Analysis”. See also NERA, “Recent Trends in Securities Class Action Litigation: 2023 Full-Year Review.” ↑